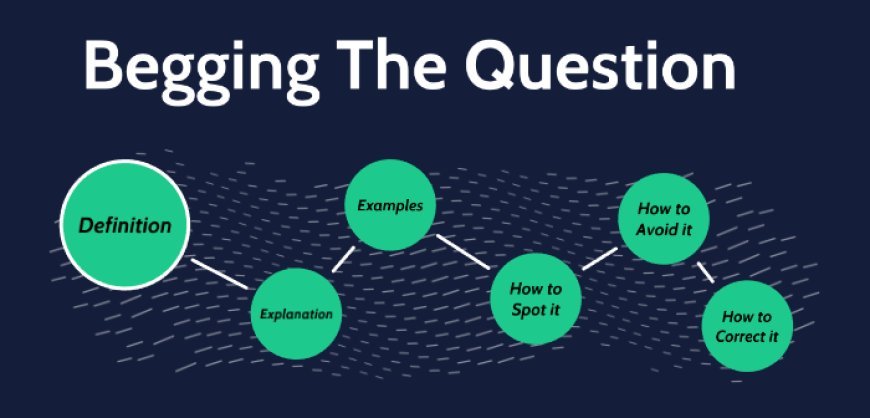

Begging the Question

This fallacy doesn't involve a logical error in the form of the argument wordings (like a non-sequitur). Instead, it's an epistemic flaw: the premises, while perhaps logically leading to the conclusion, don't offer any new information or independent justification for that conclusion. The argument simply goes in a circle, starting and ending with the same point.

The Begging the Question fallacy, also known as Circular Reasoning (Petitio Principii in Latin), is a logical fallacy where the conclusion of an argument is already assumed in one of its premises. Essentially, the argument re-states the conclusion in different wordings as if it were evidence, rather than providing independent support for it. It creates an illusion of support by using the very point that needs to be proven as a foundational truth.

The Core Mechanism of Begging the Question

The structure of Begging the Question typically looks like this:

- Premise X (which is essentially the conclusion in disguise or requires the conclusion to be true).

- Therefore, Conclusion X.

The fundamental flaw is that the argument provides no genuine evidence. It assumes the very thing it's trying to prove. The premises are often just a rephrasing of the conclusion, perhaps using synonyms or a slightly different grammatical structure, but conveying the exact same idea.

The wordings that are characteristic of begging the question often involve:

- Synonymous restatement: The premise is just the conclusion stated differently.

- Assuming what needs to be proven: A key part of the conclusion is treated as an accepted truth in a premise.

- Circular definition: Defining a term by using the term itself or a concept that relies on the term.

- "Because it is..." or "Because it must be..." without further justification.

These wordings create a closed loop where the justification is self-referential, offering no external support for the claim.

Examples of Begging the Question (Circular Reasoning)

This fallacy can be subtle, especially when the circle of reasoning is large or uses complex wordings.

-

Direct Restatement/Synonymy:

- Example 1: "God exists because the Bible says so, and the Bible is true because it is the word of God."

- Analysis: The conclusion ("God exists") is used to justify the premise ("Bible is true because it's God's word"), which in turn justifies the conclusion. It's a perfect circle. The wordings are different, but the ideas are interdependent.

- Example 2: "Smoking is bad for your health because it harms your body."

- Analysis: "Bad for your health" and "harms your body" are essentially synonymous. The argument doesn't provide new information or evidence (like specific diseases caused by smoking); it just states the same idea twice. The wordings are interchangeable here.

- Example 3: "Killing people is wrong because it is morally impermissible to take a human life."

- Analysis: "Wrong" and "morally impermissible" are equivalent. The argument doesn't explain why it's wrong or impermissible; it merely rephrases the claim.

- Example 1: "God exists because the Bible says so, and the Bible is true because it is the word of God."

-

Assuming the Conclusion in a Premise:

- Example 1: "Free speech is good because allowing people to speak freely is always beneficial to society."

- Analysis: The premise ("allowing people to speak freely is always beneficial") already assumes the goodness/benefit of free speech, which is the very thing the argument is trying to prove. It doesn't offer independent reasons for why it's beneficial.

- Example 2: "The defendant is guilty because he committed the crime."

- Analysis: To say someone "committed the crime" is to say they are "guilty." The premise assumes the conclusion. What needs to be proven is how we know he committed the crime.

- Example 3: "Of course, ghosts are real. I saw one last night with my own eyes, and my eyesight is excellent, so I definitely saw a ghost."

- Analysis: The conclusion ("ghosts are real") is assumed in the premise ("I saw one") which is then 'supported' by the quality of eyesight, but the initial premise relies on the ghost being real.

- Example 1: "Free speech is good because allowing people to speak freely is always beneficial to society."

-

Circular Definitions:

- Example: "What is gravity?" "Gravity is the force that pulls things down." "What does 'pulls things down' mean?" "It means gravity is acting on them."

- Analysis: The definition relies on the term itself or a concept explained by the term, providing no new understanding. The wordings go in a definitional circle.

- Example: "What is gravity?" "Gravity is the force that pulls things down." "What does 'pulls things down' mean?" "It means gravity is acting on them."

-

Complex or Extended Circularity (Vicious Circles):

- Sometimes, the circle of reasoning isn't just A explains B and B explains A, but A explains B, B explains C, and C explains A.

- Example: "The stock market is going up because investors have confidence. Investors have confidence because the stock market is going up."

- Analysis: The two statements define and reinforce each other without external justification for why either is happening initially. The wordings create a self-sustaining, but unproven, loop.

Why Begging the Question is Persuasive (and Dangerous)

Begging the Question can be persuasive because:

- It Sounds Logical: The conclusion does follow from the premise, making it appear to be a valid argument. The logical structure itself isn't broken, just the informative content.

- Concealed Premise: The circularity can be difficult to spot, especially if the premise is a rephrasing or if the argument is long and complex. The wordings can cleverly disguise the tautology.

- Reinforces Existing Beliefs: If the audience already believes the conclusion, they might not notice that the argument offers no new evidence for it; it merely confirms what they already accept.

- Dogmatic Assertion: It can give the impression of a confident, unquestionable truth, making it seem like there's nothing left to discuss.

The danger of begging the question is that it halts genuine inquiry and debate. It prevents the exploration of true justifications or counter-evidence.

- Prevents Deeper Understanding: If the reason for something is just a restatement of the thing itself, no real insight is gained.

- Stifles Criticism: If you challenge a premise that is actually the conclusion, the arguer can simply point to the conclusion as "proof."

- Supports Unfounded Claims: It allows claims to stand without any real empirical or logical backing. It can be used to defend deeply held, but ultimately unproven, beliefs.

- Leads to Stagnation: In fields requiring progress (like science or policy), circular reasoning prevents moving forward by continually circling back to unproven assumptions.

Identifying and Countering Begging the Question

To identify Begging the Question, carefully examine the premises of an argument. Ask yourself:

- Does this premise already assume the truth of the conclusion?

- Is the premise just a different way of saying the conclusion?

- Would someone who doesn't already believe the conclusion also believe this premise without further proof? If not, it's likely begging the question.

Pay attention to the wordings – are they truly distinct pieces of information or just synonyms/rephrasing?

To effectively counter Begging the Question:

- Point Out the Circularity: Explain that the argument uses the conclusion as its own evidence.

- Example Counter: "Your argument that X is true because Y is true, and Y is true because X is true, is circular. You're assuming what you're trying to prove."

- Using "wordings" to highlight the circularity: "The wordings you've used for your premise and conclusion are essentially the same, meaning your argument circles back on itself without providing independent proof."

- Challenge the Premise: Refuse to accept the premise as true until it is supported by independent evidence, separate from the conclusion.

- Example Counter: "You're saying that free speech is beneficial because allowing people to speak freely is beneficial. But why is allowing people to speak freely beneficial? That's the part that needs to be proven."

- Ask for External Evidence: Demand new, non-circular evidence or reasoning that would truly support the claim.

- Example Counter: "What independent evidence can you provide that supports the idea that the Bible is the word of God, beyond its own claims?"

- Rephrase the Argument to Expose the Flaw: Articulate the argument in a way that makes its circularity obvious.

- Example Counter: "So, what you're essentially saying is 'X is true because X is true.' That doesn't give us any reason to believe it."

- Distinguish Between Argument and Assertion: Explain that the arguer is merely asserting their conclusion, not arguing for it.

- Example Counter: "You're asserting that free speech is good, but you haven't given any reasons why it's good; you've just restated that it's good."

By identifying the self-referential nature of the premises and demanding true, independent justification, you can expose the emptiness of a circular argument and push for actual evidence and logical support. This is crucial for distinguishing genuine arguments from mere assertions.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0