Argumentum ad Populum (The Appeal to Popularity)

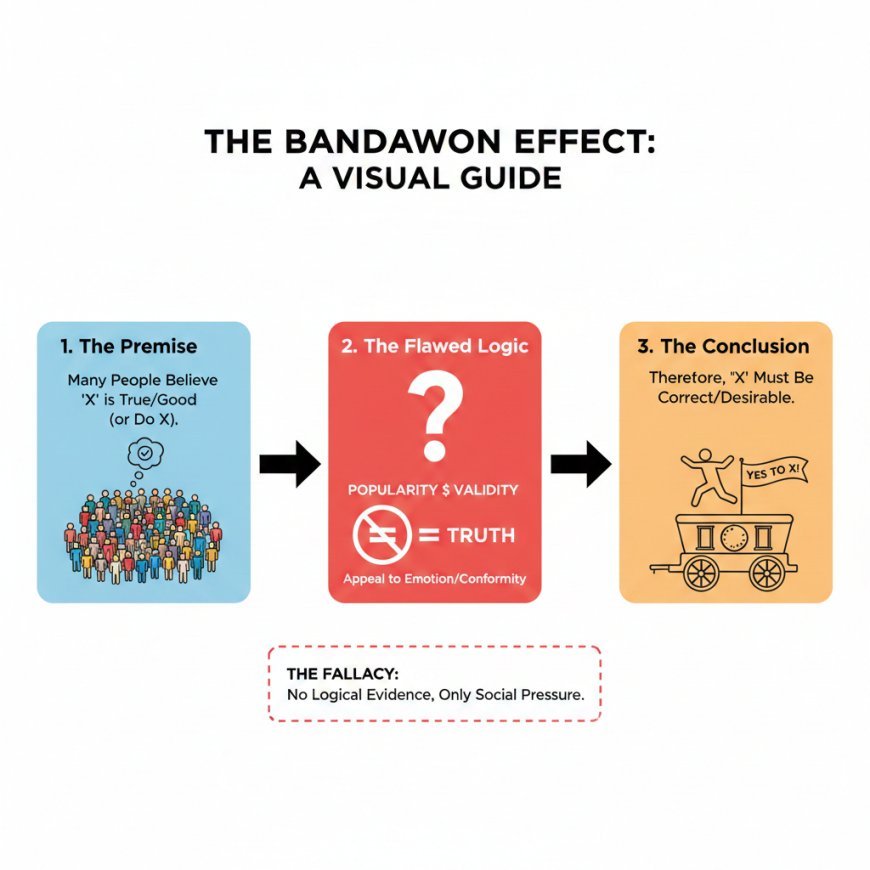

At its heart, the bandwagon fallacy equates popularity with validity or truth. It sidesteps the need for logical justification by suggesting that the sheer number of adherents is sufficient proof.

The Bandwagon fallacy, formally known as Argumentum ad Populum (Latin for "argument to the people" or "appeal to the populace"), is a logical fallacy that asserts a claim is true or good simply because many people believe it or do it. It operates on the principle of popular appeal: if "everyone else is doing it" or "everyone believes it," then it must be correct, desirable, or valid. The fallacy attempts to persuade by appealing to the desire to belong, to be accepted, or to conform, rather than by providing logical evidence or reasoned arguments.

The Core Mechanism of the Bandwagon Fallacy

The structure of a bandwagon argument typically looks like this:

- Many people (the majority, "everyone," "most people") believe X is true/good, or do X.

- Therefore, X must be true/good, or should be done.

The fundamental flaw is that the popularity of an idea or action has no bearing on its truth, morality, or validity. Throughout history, popular beliefs have often been proven false, and widely adopted practices have been shown to be harmful. Truth is determined by evidence and logic, not by majority opinion.

The wordings that are characteristic of the bandwagon fallacy often include phrases that emphasize widespread acceptance or trends:

- "Everyone knows that..."

- "Most people agree..."

- "Join the millions who..."

- "Don't be left out; everyone else is doing it!"

- "The majority supports..."

- "It's the most popular choice, so it must be the best."

- "Clearly, the public consensus is..."

These wordings are designed to create social pressure, implying that to disagree or not conform is to be an outlier, misinformed, or socially unacceptable

| The Hook (What They Say) | The Psychological Lever (What They Mean) |

| "Join the millions who..." or "Everyone knows that..." | You are isolated or ignorant if you disagree. |

| "The most popular choice, so it must be the best." | Choosing anything else means settling for inferior quality. |

| "Don't be left out; everyone else is doing it!" | You risk exclusion or missing a vital trend. |

| "Polls show 70% support..." or "Most people agree..." | The sheer number of believers validates the claim. |

Types and Examples of Bandwagon Fallacies

The bandwagon fallacy is pervasive in various forms of communication, particularly in advertising, politics, and social pressure:

Advertising and Consumerism:

-

- Example 1: "Nine out of ten doctors recommend Brand X toothpaste. It must be the best choice for your oral health!"

- Analysis: While a high recommendation rate could indicate quality, the fallacy lies in implicitly suggesting that the sheer number of doctors recommending it proves it's the best, without providing scientific evidence of its superiority (e.g., studies, ingredients analysis). The wordings emphasize the numerical majority.

- Example 2: "Don't get left behind! Everyone is upgrading to the new 'GamerPro X' console this holiday season. Get yours now!"

- Analysis: The appeal is purely to popularity and the fear of missing out (FOMO), not to the console's actual features, performance, or value. The implied message is: if everyone else is doing it, you should too.

- Example 1: "Nine out of ten doctors recommend Brand X toothpaste. It must be the best choice for your oral health!"

Politics and Public Opinion:

-

- Example 1: "Polls show that 70% of the public supports this new policy. Clearly, it's the right direction for our country."

- Analysis: While public opinion can be relevant in a democracy, the mere fact that a majority supports a policy does not automatically make it sound, ethical, or effective. The policy's merits (or demerits) must be evaluated on their own terms. The wordings leverage statistics to imply correctness.

- Example 2: "My opponent's ideas are unpopular and out of touch with what the average person believes. Therefore, they are wrong."

- Analysis: Popularity does not equate to correctness. Historically, many groundbreaking or morally just ideas were initially unpopular. This shifts the focus from the validity of the ideas to their public reception

- Example 1: "Polls show that 70% of the public supports this new policy. Clearly, it's the right direction for our country."

Social Trends and Peer Pressure:

-

-

-

- Example 1: "Everyone is wearing these new fashion trends. If you don't wear them, you'll be considered uncool."

- Analysis: This uses social pressure to dictate behavior or choices, implying that conformity is necessary for acceptance. "Uncool" is the implied negative consequence for not joining the bandwagon.

- Example 2: "Most of my friends are trying this new diet, and they're all losing weight. I should definitely try it too; it must work."

- Analysis: The argument relies on peer behavior rather than individual suitability, scientific evidence for the diet's long-term effectiveness, or consideration of potential health risks. The wordings tie personal decision-making to group activity

- Example 1: "Everyone is wearing these new fashion trends. If you don't wear them, you'll be considered uncool."

-

-

Historical and Cultural Context:

-

- Example 1: "People have believed in X for centuries. It wouldn't have lasted this long if it weren't true."

- Analysis: The longevity of a belief does not guarantee its truth (e.g., geocentric model of the universe, slavery, witch hunts were long-held beliefs). This is a form of appeal to tradition, which often overlaps with bandwagon.

- Example 2: "In our culture, it has always been understood that Y is the proper way to behave, so it must be correct."

- Analysis: Cultural norms change, and historical or traditional practices are not inherently morally correct simply because they are long-standing or widely accepted within a particular group

- Example 1: "People have believed in X for centuries. It wouldn't have lasted this long if it weren't true."

| Domain of Appeal | Primary Objective |

| Consumerism (Advertising) | To drive immediate purchases and market dominance. |

| Public Opinion (Politics) | To secure electoral support and normalize controversial ideas. |

| Social Trends (Peer Pressure) | To dictate behavior and enforce aesthetic standards. |

Why Bandwagon Fallacies are Persuasive (and Dangerous)

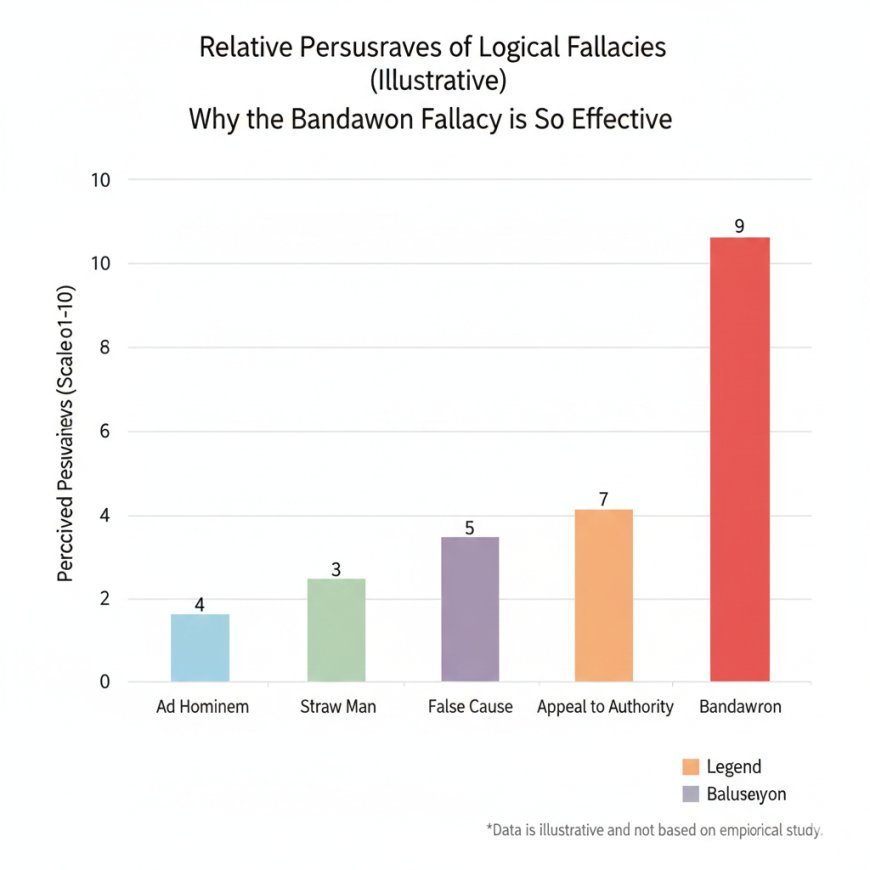

The bandwagon fallacy is highly effective because it taps into fundamental human psychological needs and tendencies:

- Desire for Conformity and Belonging: Humans are social creatures who naturally desire acceptance and fear exclusion. The fallacy exploits this by suggesting that conformity to the majority leads to belonging. The wordings often play on the fear of being "left out" or "different."

- Social Proof: People often look to others for cues on how to behave or what to believe, especially in uncertain situations. If "everyone" is doing it, it creates a sense of safety and validation.

- Lazy Thinking: It's easier to simply follow the crowd than to critically evaluate an argument or make an independent decision.

- Fear of Being Wrong/Isolated: Disagreeing with the majority can feel daunting and may lead to social ostracization or the perception of being irrational.

- Perceived Authority of the Majority: The sheer number of people holding a belief can mistakenly be interpreted as a form of collective authority or evidence.

The danger of the bandwagon fallacy is significant. It can lead to:

- Herd Mentality: People making poor decisions or adopting harmful beliefs simply because they are popular, without critical thinking.

- Suppression of Dissent: Individuals might be discouraged from expressing dissenting opinions, even if those opinions are well-reasoned, for fear of being seen as outsiders.

- Stagnation: Resistance to new ideas or progress simply because they are not yet widely accepted.

- Moral Relativism (of a sort): If truth or goodness is determined by popular opinion, then objective standards can be eroded.

- Exploitation by Demagogues: Populist leaders can use this fallacy to rally support for ideas that lack substance but appeal to mass sentiment.

Identifying and Countering the Bandwagon Fallacy

To identify a bandwagon fallacy, listen for wordings that emphasize popularity, majority opinion, or widespread adoption as the primary reason for a claim's validity. Ask yourself: Is the argument based on logical evidence and reasoning, or is it simply appealing to the idea that "everyone is doing/believing it"?

To effectively counter a Bandwagon fallacy:

- Separate Popularity from Truth/Validity: Directly point out that popularity does not equate to correctness.

- Example Counter: "The fact that many people believe X doesn't automatically make X true. We need to look at the evidence for X itself."

- Using "wordings" to make the distinction: "Your wordings imply widespread agreement means correctness, but those are two different things."

- Demand Logical Evidence: Shift the focus back to the substance of the argument by asking for reasons beyond popular appeal.

- Example Counter: "Instead of how many people support this policy, can we discuss the actual economic benefits and drawbacks?"

- Provide Counter-Examples (Historical or Contemporary): Cite instances where popular beliefs or actions were later proven false or harmful.

- Example Counter: "Throughout history, there have been many times when the majority was wrong. Remember when everyone believed the earth was flat?"

- Emphasize Independent Thought: Encourage critical thinking and individual evaluation of the evidence.

- Example Counter: "My decision won't be based on what everyone else is doing, but on what the facts and logic suggest."

- Expose the Underlying Social Pressure: Point out that the argument is using social pressure rather than rational persuasion.

- Example Counter: "You're trying to appeal to my desire to fit in, but that's not a valid reason to accept a claim."

- "Truth is Not a Democracy": A concise phrase to encapsulate the counter.

- Example Counter: "Truth isn't determined by popular vote; it's determined by evidence."

By challenging the notion that popularity dictates truth or correctness, you can dismantle the bandwagon fallacy and promote a more rational approach to evaluating claims and making decisions, encouraging genuine conviction over mere conformity.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0