False Dilemma

The False Dilemma fallacy, also known as the False Dichotomy or Either/Or fallacy, occurs when an arguer presents only two options or choices as if they are the only possibilities, when in fact, more valid alternatives exist.

This tactic attempts to force a choice between two extremes, often one desirable and one undesirable, thereby leading the audience to believe that the only logical conclusion is to choose the preferred option. It simplifies a complex reality into a misleading binary, ignoring the nuanced spectrum of possibilities that usually characterizes real-world situations.

The essence of the fallacy lies in its artificial restriction of choices. It creates a tunnel vision, making it seem as though there are only two paths forward, leaving no room for compromise, alternative solutions, or even neutrality.

The Core Mechanism of the False Dilemma

The structure of a false dilemma argument is straightforward:

- Either A is true, or B is true.

- (Implicitly or explicitly) A is undesirable/false.

- Therefore, B must be true/chosen.

The flaw here is the initial premise: the assumption that A and B are the only two possibilities, and that they are mutually exclusive (cannot both be true) and collectively exhaustive (cover all possibilities). In reality, there might be options C, D, or even a blend of A and B that are viable. The fallacy ignores these other possibilities, creating a "forced choice" scenario.

The wordings that signal a false dilemma are often direct and forceful:

- "You're either with us or against us."

- "It's either X or Y; there's no middle ground."

- "We must choose between A and B."

- "If you're not part of the solution, you're part of the problem."

- "America: Love it or leave it."

- "There are only two kinds of people in the world: those who..."

These wordings impose a rigid, binary framework on a situation that is inherently more fluid and multifaceted.

Types and Examples of False Dilemmas

False dilemmas manifest in various contexts, often in attempts to simplify debates or create a sense of urgency:

-

Political Rhetoric: A common tool to polarize debates and rally support.

- Example 1: "Either we drastically cut taxes to stimulate the economy, or we face economic collapse. There's no other way."

- Analysis: This ignores numerous other economic strategies like targeted investments, infrastructure spending, gradual tax adjustments, or varying levels of regulation, all of which could also impact the economy without necessarily leading to collapse.

- Example 2: "In this election, you can either vote for freedom and prosperity, or for socialism and ruin. The choice is clear."

- Analysis: This implies that only two political ideologies exist, and that one leads solely to positive outcomes while the other leads solely to disaster, ignoring the complexities of political platforms and the wide spectrum of beliefs. The wordings here are highly emotive, designed to push the audience towards one side.

- Example 1: "Either we drastically cut taxes to stimulate the economy, or we face economic collapse. There's no other way."

-

Moral and Ethical Debates: Used to force a stance on complex issues.

- Example 1: "Either we allow unlimited free speech, or we become a totalitarian state that suppresses dissent."

- Analysis: This ignores the possibility of reasonable limits on free speech (e.g., incitement to violence, defamation) that exist in many democratic societies without leading to totalitarianism. There's a wide middle ground of regulated free speech.

- Example 2: "You must either believe in absolute good and evil, or you are a moral relativist with no principles."

- Analysis: This ignores various ethical frameworks that acknowledge moral complexity without abandoning principles, such as virtue ethics, utilitarianism, or deontology, which allow for nuanced moral reasoning.

- Example 1: "Either we allow unlimited free speech, or we become a totalitarian state that suppresses dissent."

-

Personal Decisions and Lifestyle: Often seen in persuasive appeals.

- Example 1: "You either spend all your time studying to get perfect grades, or you'll fail out of college. There's no in-between."

- Analysis: This ignores the possibility of balanced effort leading to good grades, or prioritizing other aspects of college life while still passing courses.

- Example 2: "You either love our product, or you simply don't understand what real quality is."

- Analysis: This attempts to shame the consumer into conformity by implying that any dislike stems from ignorance, ignoring valid reasons for preference or objective assessment of quality.

- Example 1: "You either spend all your time studying to get perfect grades, or you'll fail out of college. There's no in-between."

-

Problem Solving: Used to present a limited range of solutions.

- Example: "We can either cut the budget drastically or lay off a large number of employees. Those are our only options to save the company."

- Analysis: This overlooks other potential solutions like seeking new revenue streams, negotiating with suppliers, restructuring departments, or implementing temporary cost-saving measures without layoffs.

- Example: "We can either cut the budget drastically or lay off a large number of employees. Those are our only options to save the company."

Why False Dilemmas are Persuasive (and Dangerous)

False dilemmas are surprisingly effective because they:

- Simplify Complexity: Human minds often seek simplicity. A false dilemma provides a clear, seemingly straightforward choice in a complex world.

- Create Urgency/Fear: By presenting one option as catastrophic, it instills fear, pushing the audience to choose the "safe" alternative. The wordings frequently amplify the negative consequences of the rejected option.

- Manipulate Decision-Making: They force individuals into a pre-determined decision by limiting their perceived options.

- Control the Narrative: By defining the available choices, the arguer dictates the terms of the debate, steering the conversation away from inconvenient alternatives.

- Exploit Black-and-White Thinking: Many people are susceptible to thinking in binaries, making the false dilemma resonate with their cognitive patterns.

The danger of the false dilemma is significant. It limits critical thought and stifles creativity in problem-solving. It can lead to bad decisions by eliminating superior alternatives. In public discourse, it fosters polarization and prevents compromise by framing issues as battles between absolute opposites rather than opportunities for nuanced solutions. It can also be used to justify extreme actions by making them seem like the only alternative to an even worse outcome.

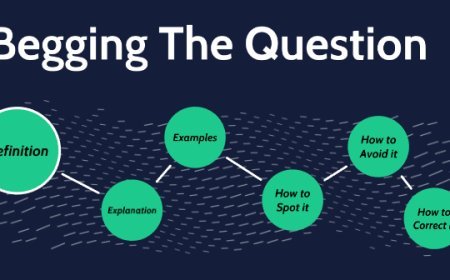

Identifying and Countering the False Dilemma

Identifying a false dilemma requires a critical eye for absolute wordings that suggest only two possibilities: "either/or," "only choice," "no middle ground." When confronted with such a choice, immediately ask yourself: Are these truly the only options?

To effectively counter a False Dilemma fallacy:

- Expose the Hidden Options: The most direct way to counter is to point out that there are other possibilities beyond the two presented.

- Example Counter: "Actually, there's a third option/several other options that haven't been considered."

- Using "wordings" to highlight the oversight: "The wordings of your argument create a false binary. We're not limited to just X or Y."

- Introduce a "Third Way" or "Middle Ground": Explicitly state and briefly explain one or more viable alternatives.

- Example Counter: "Instead of drastically cutting taxes or facing economic collapse, we could look at targeted investments in infrastructure and education, which could also stimulate growth."

- For "You're either with us or against us": "I can be 'with you' on the principle of the matter, but have reservations about the specific methods, and still contribute positively. It's not a binary choice of complete allegiance or opposition."

- Challenge the Exclusivity or Exhaustiveness: Question why the presented options are considered the only ones.

- Example Counter: "Why do you believe these are the only two choices? What assumptions are you making that exclude other solutions?"

- Reframe the Issue: Broaden the scope of the discussion to include complexity and multiple perspectives.

- Example Counter: "This isn't just about 'freedom vs. socialism'; it's about finding the best balance of individual liberty and collective well-being, and there are many different approaches to that."

- Seek Nuance: Emphasize that issues are rarely black and white.

- Example Counter: "Life is rarely either/or. Most situations involve a spectrum of possibilities and trade-offs."

- Use a Counter-Example or Analogy: Illustrate the absurdity of the limited choice in a different context.

- Example Analogy: "That's like saying you either only eat apples or you starve. There are clearly many other kinds of food!"

By successfully demonstrating that the presented choice is artificially limited, you dismantle the false dilemma and open up the possibility for more rational, comprehensive, and creative solutions. This allows for a more realistic and productive discussion where all viable options can be considered.

Want to know more about fallacies? Click here to read about Appeal to Popular Opinion

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0