Hasty Generalization

This fallacy is a prime example of flawed inductive reasoning, where specific observations are used to infer a general rule. While inductive reasoning is essential for learning and discovery, it becomes fallacious when the inference is made too quickly or without adequate support, leading to conclusions that are not justified by the premises.

The Hasty Generalization fallacy, also known as the Fallacy of Insufficient Statistics, Faulty Generalization, or Argument from Small Sample, occurs when an arguer draws a broad conclusion about an entire group, category, or phenomenon based on a sample that is too small, unrepresentative, or atypical. Instead of gathering enough evidence to support a sweeping claim, the arguer makes a rapid leap from a few observations to a universal truth, often with significant consequences for accuracy and fairness.

The Core Mechanism of the Hasty Generalization

The structure of a hasty generalization typically looks like this:

- I have observed X (a small number of instances or a specific case) that has characteristic Y.

- Therefore, all Xs (the entire group/category) must have characteristic Y.

The fundamental flaw here is the leap from "some" or "a few" to "all" or "every." The sample size is insufficient to support the universal claim. The observation might be true for the specific instances, but it is fallacious to generalize that truth to an entire population without further evidence.

The wordings that often signal a hasty generalization are generalizations that lack qualifying phrases, such as:

- "All X are Y."

- "Every time I see a Z, it's like this."

- "People from [specific place] are always [characteristic]."

- "I know a few [professionals], and they are all [negative trait]."

- "Based on my experience, [broad conclusion]..."

- "You can't trust [group of people], because..."

These wordings present anecdotal evidence or limited experiences as definitive proof for sweeping, universal statements.

Examples of Hasty Generalization

Hasty generalizations are incredibly common in everyday conversations, often contributing to stereotypes and prejudice:

-

Personal Experiences as Universal Truths:

- Example 1: "I've visited New York City twice, and both times the taxi drivers were rude. Clearly, all New York City taxi drivers are rude."

- Analysis: Two observations are an incredibly small and unrepresentative sample to generalize about thousands of taxi drivers. The wordings here move directly from "both times" to "all."

- Example 2: "My grandmother tried that new herbal supplement, and it made her feel great. Herbal supplements must be effective for everyone."

- Analysis: A single positive anecdotal experience is not sufficient to conclude universal effectiveness. There are many factors at play, including the placebo effect, and individual variations.

- Example 1: "I've visited New York City twice, and both times the taxi drivers were rude. Clearly, all New York City taxi drivers are rude."

-

Stereotyping and Prejudice: This fallacy is a backbone of discriminatory thinking.

- Example 1: "I had a bad experience with one person from Country A; they were very pushy. Therefore, everyone from Country A is pushy."

- Analysis: Generalizing negative traits from one or a few individuals to an entire nationality or ethnic group is a classic hasty generalization, forming the basis of stereotypes. The wordings are sweeping: "everyone."

- Example 2: "That brand of car broke down on me after only two years. All cars from that manufacturer are unreliable junk."

- Analysis: One faulty car (even if truly faulty) is not enough evidence to judge the reliability of an entire production line or manufacturer's output. Many other factors could have been at play.

- Example 1: "I had a bad experience with one person from Country A; they were very pushy. Therefore, everyone from Country A is pushy."

-

Media and Anecdotal Reporting:

- Example 1: "I read a news story about a few politicians accepting bribes. Clearly, all politicians are corrupt and only care about money."

- Analysis: While corruption exists, generalizing it to all politicians based on a few reported cases is a hasty generalization. The media often highlights exceptions.

- Example 2: "I saw a viral video of one student acting violently at a school. Our schools are becoming unsafe and chaotic."

- Analysis: A single, possibly unusual, event in a school does not mean that all schools are generally unsafe or that violence is rampant.

- Example 1: "I read a news story about a few politicians accepting bribes. Clearly, all politicians are corrupt and only care about money."

-

Scientific/Research Context (Less Common in Rigorous Work, but a Risk):

- While good scientific methodology guards against this, an amateur interpretation might fall prey.

- Example: "Our initial small pilot study showed promising results for Drug X in 5 patients. This drug will cure everyone with this condition!"

- Analysis: Promising pilot results necessitate larger, controlled studies. Generalizing from 5 patients to "everyone" is a hasty generalization, as factors like patient selection bias, small sample size, and lack of control groups make such a broad claim unsupported.

Why Hasty Generalizations are Persuasive (and Dangerous)

Hasty generalizations can be persuasive because they:

- Offer Simple Explanations: Complex realities are simplified into easy-to-digest, seemingly universal truths.

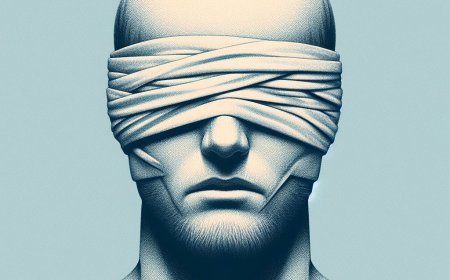

- Confirm Biases: If a generalization aligns with existing prejudices or beliefs, people are more likely to accept it without critical scrutiny.

- Appeal to Anecdotal Evidence: Personal stories or vivid examples can be very compelling, even if they are not statistically significant. The wordings often present these anecdotes as if they are universal proof.

- Cognitive Efficiency: It's easier for the brain to categorize and generalize quickly than to process every individual piece of information with nuance.

The danger of hasty generalizations is profound. They are a primary source of stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination. By falsely attributing characteristics to entire groups, they can:

- Fuel social division: Creating "us vs. them" narratives based on insufficient evidence.

- Lead to unfair judgments: Individuals are judged not on their own merits but on presumed characteristics of a group they belong to.

- Obscure truth and nuance: Complex social issues, human behavior, or scientific phenomena are oversimplified.

- Result in poor decision-making: Policies or actions might be based on flawed assumptions about groups of people or circumstances, rather than on accurate data.

- Promote confirmation bias: Once a generalization is made, individuals tend to selectively notice evidence that confirms it, ignoring contradictory information.

Identifying and Countering the Hasty Generalization

To identify a hasty generalization, pay attention to the wordings that make universal claims ("all," "every," "always," "never") based on very limited observations. Ask yourself: Is the sample size large enough? Is it diverse and representative of the whole group?

To effectively counter a Hasty Generalization fallacy:

- Challenge the Sample Size: Point out that the evidence presented is too small to support the broad conclusion.

- Example Counter: "You're basing that sweeping statement about all taxi drivers on only two experiences. That's not enough to draw such a conclusion."

- Using "wordings" to highlight the inadequacy: "Your wordings suggest universal truth, but your sample size is extremely limited."

- Question the Representativeness: Argue that the observed instances might be atypical or not representative of the entire group.

- Example Counter: "The few news stories you've seen about corrupt politicians don't reflect the majority who serve ethically. Those are often highlighted because they're exceptions."

- Provide Counter-Examples: Offer instances that contradict the generalization. Even one strong counter-example can weaken the universal claim.

- Example Counter: "While you had a bad experience, I know many New York City taxi drivers who are incredibly friendly and helpful."

- Demand More Evidence: Ask for more comprehensive data, studies, or observations that would genuinely support such a broad claim.

- Example Counter: "To make such a strong claim about an entire group, you'd need much more substantial evidence than just a few personal anecdotes."

- Distinguish Between "Some" and "All": Clarify the difference between specific observations and universal claims.

- Example Counter: "It's fair to say that some politicians might be corrupt, but it's a huge leap to claim that all of them are based on that."

By challenging the jump from limited evidence to sweeping conclusions, you can expose the flaw in a hasty generalization and promote a more accurate and nuanced understanding of the world. This is crucial for overcoming biases and fostering fairer judgments.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0